Rose Gardner is not giving up.

A Eunice resident, Gardner has spent the past few years fighting a proposal to store high-level nuclear waste in southeastern New Mexico.

“I was born here in Eunice, New Mexico, and have lived through a lot of ups and downs, oil booms and busts,” Gardner told NM Political Report. “But never have I ever felt that we needed an industry as dangerous as storing high-level nuclear waste right here.”

Gardner, who co-founded the Alliance for Environmental Strategies, is part of a groundswell of opposition to a project currently under consideration by the federal Nuclear Regulatory Commission (NRC) that would see the world’s largest nuclear waste storage facility be built along the Lea-Eddy county line.

Holtec International, a private company specializing in spent nuclear fuel storage and management, applied for a license from the NRC in 2017 to construct and operate the facility in southeastern New Mexico that would hold waste generated at nuclear utilities around the country temporarily until a permanent, federally-managed repository is established. The license application is making steady progress in the NRC’s process, despite the pandemic.

Proponents of the project tout the estimated $3 billion in capital investments and 100 new jobs that it would bring to the area. But opponents — including the governor of New Mexico, most tribal nations in the state, state lawmakers, 12 local governments and a number of local associations — worry that the proposed interim storage facility would become a de facto permanent storage solution for the nation’s growing nuclear waste.

“There’s a great concern that this waste, should it end up in New Mexico, will really never move from here,” state Sen. Jeff Steinborn, D-Las Cruces, told NM Political Report. “A facility that’s not designed to be forever, suddenly becomes forever. That’s really bad for New Mexico. That’s not in our interest at all.”

Seeking a home for the nation’s nuclear waste

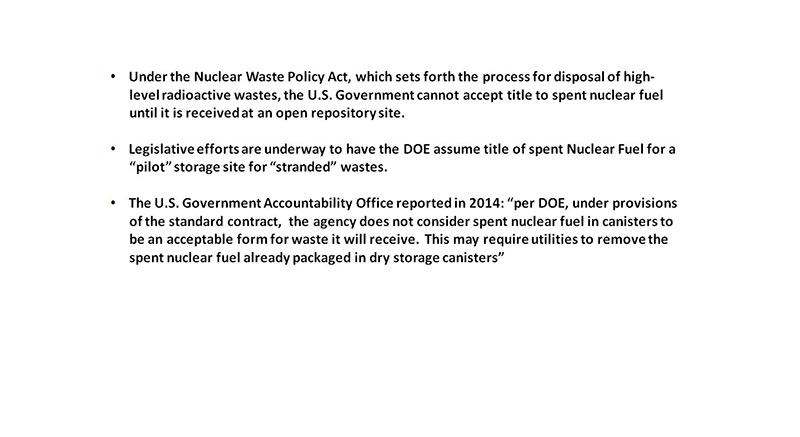

The United States has a growing nuclear waste problem and no permanent solution in sight. In the early 1980s, Congress passed the Nuclear Waste Policy Act, which designated underground repositories as the national strategy for permanent storage of spent nuclear fuel.

After a years-long back-and-forth between federal agencies and scientists over the parameters needed to safely and permanently store spent nuclear fuel in perpetuity, the government settled on the Yucca Mountain site, a volcanic structure located in Nevada, as the national repository. But the project was scrapped under former President Barack Obama, in part because a geologic assessment of the area raised questions of the long-term safety of housing the waste there.

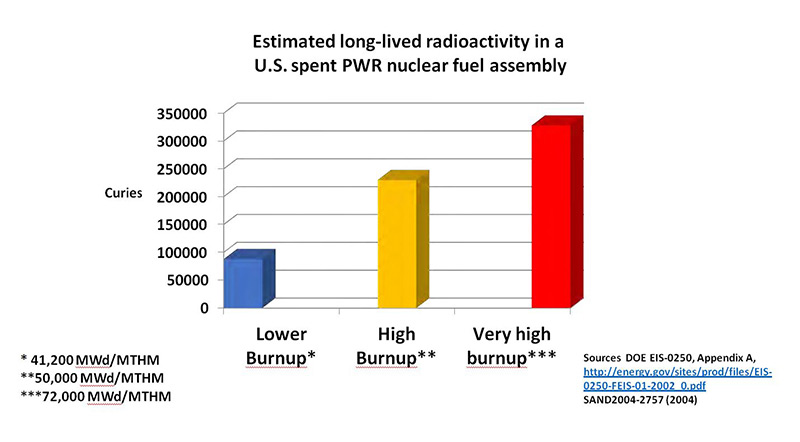

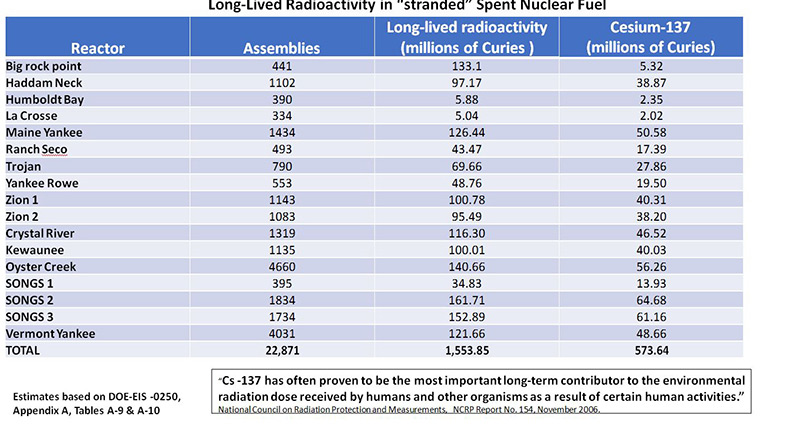

“This is the dilemma. It’s deadly for at least a million years, it’s actually deadly for much longer. Human beings have never devised a way to isolate this from the environment for that long a period of time,” said Kevin Kamps, radioactive waste specialist at Beyond Nuclear. “It raises the question, can we find geology for permanent disposal that can hold this stuff in for a million years or more?”

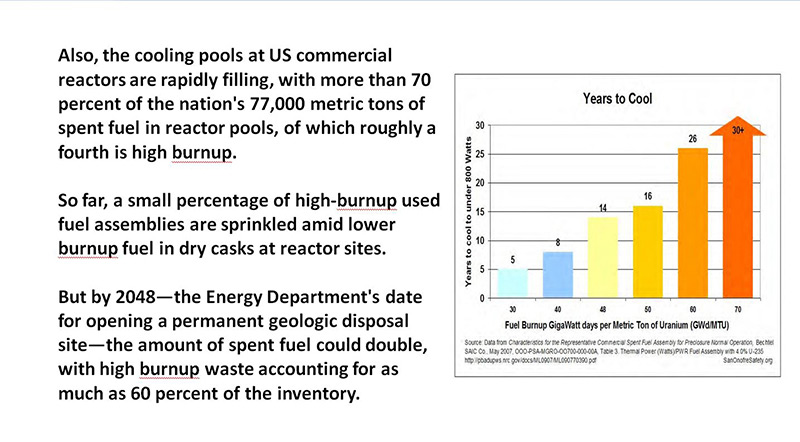

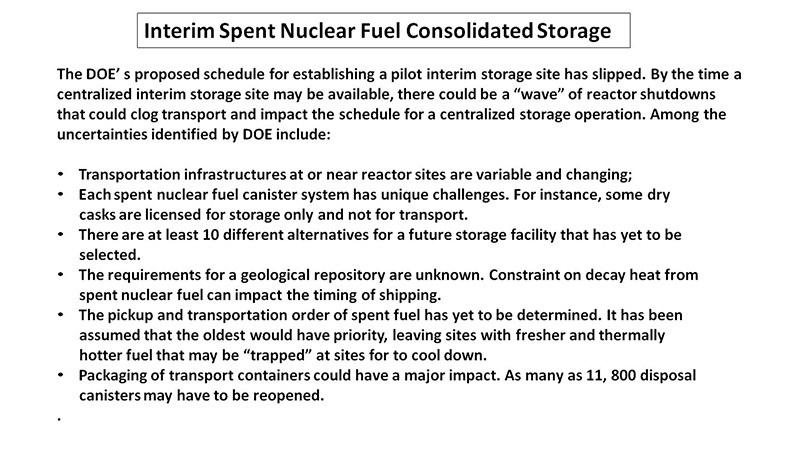

The Nuclear Waste Policy Act mandated the federal government take ownership of the waste when a permanent storage facility is established. But with no such facility in the works, the waste generated by commercial nuclear utilities is currently being stored in interim facilities at or near the power plants themselves, while nuclear utilities across the country have sued the federal government for failing to establish a permanent repository for the waste.

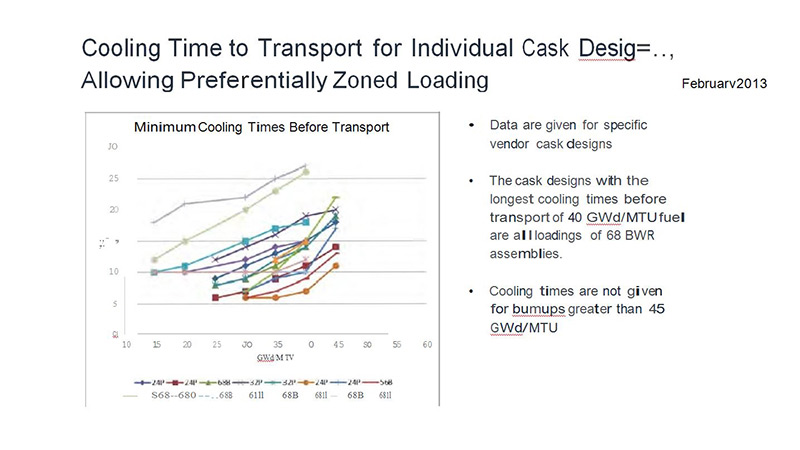

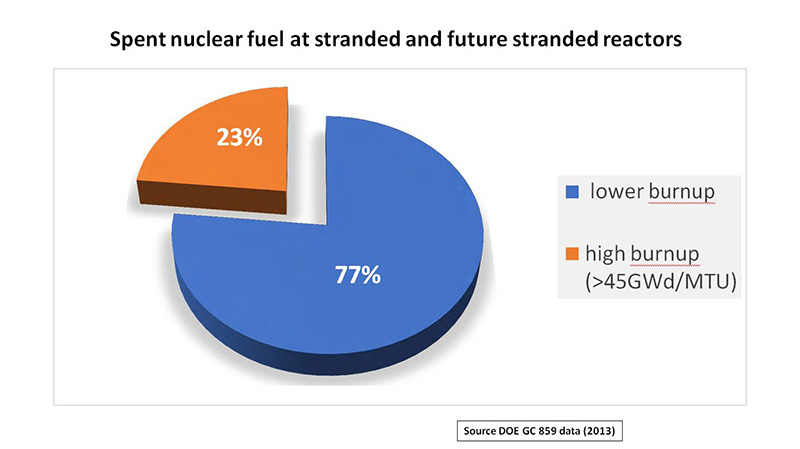

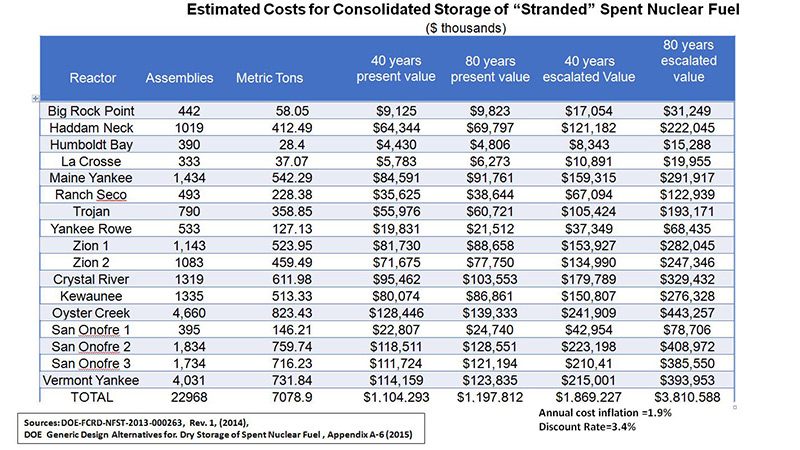

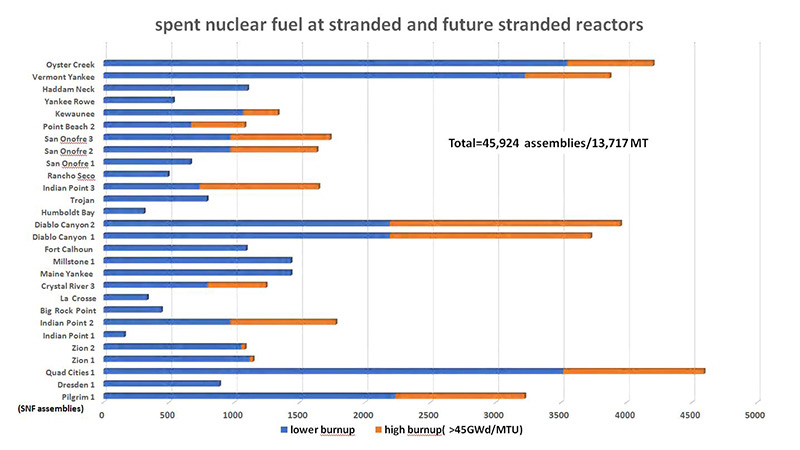

Holtec’s proposal would see waste from all the U.S. nuclear energy utilities be transported thousands of miles across the country to the proposed facility in New Mexico. The NRC is currently considering approving the license for 40 years, with an opportunity to renew the license in 40-year increments.

A spokesperson for Holtec told NM Political Report that under the proposal, Holtec would establish business relationships with the utilities who will pay Holtec to have the spent fuel stored at the proposed site, located in Lea County.

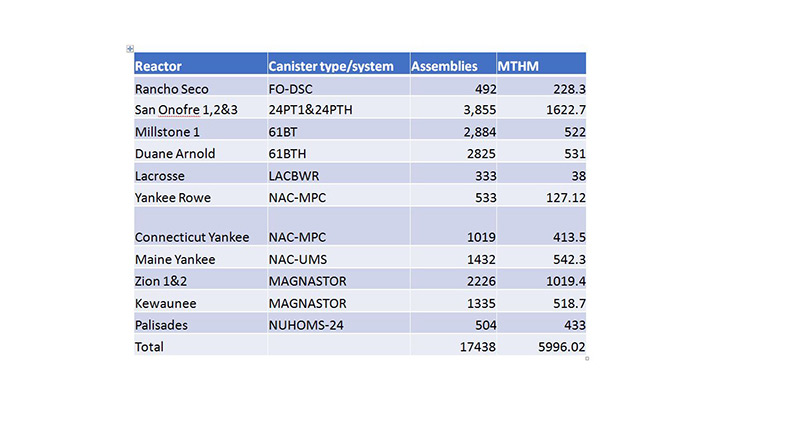

Nuclear utilities are eager to have the waste taken off their hands. The San Onofre nuclear power plant is one example. The now-defunct plant butts up against a beach in southern California, between Oceanside and San Clemente. It holds 1,600 tons of high-level nuclear waste that is currently sitting in cooling ponds at the facility, which is vulnerable both to sea level rise and seismic activity due to a nearby fault line.

Local and state politicians in California have asked for top priority to ship the fuel out of state to an interim storage facility, like the one proposed by Holtec. Kamps said that underscores another dilemma in this saga: No one wants high-level nuclear waste in their communities — including those communities that generated the waste.

Kamps pointed to the community surrounding the San Onofre plant.

“It’s one of the most glamorous places in the country,” he said. “There’s this clamor to get [the waste] out of here: ‘We don’t care where it goes, just get it out of here.’ This community made this forever deadly waste, and now wants its cake and eat it too. They want to keep all those profits that they’ve enjoyed for decades, and get rid of this forever deadly waste, make it somebody else’s problem.”

Inviting nuclear storage to New Mexico

The Eddy-Lea Energy Alliance (ELEA), an economic development partnership between Eddy and Lea counties and the cities of Hobbs and Carlsbad, has tried for years to bring more nuclear activity to the area, and the economic development that comes with it.

The alliance initially hoped to participate in the federal Global Nuclear Energy Partnership (GNEP) program, which would have collected, recycled and stored spent nuclear fuel. ELEA vice chairman John Heaton told NM Political Report the alliance acquired a piece of land for an application to participate in the GNEP program over a decade ago. GNEP was shuttered in 2009, which left the ELEA with a piece of real estate primed for nuclear storage. The alliance then pivoted towards an interim storage facility for the land.

“It really is an extraordinary location. It’s isolated, it’s 35 miles from any population; it has electricity, water, roads, rail access only four miles away. It’s 35 miles from the nearest town,” Heaton said. He added that the area already has some resident expertise in the nuclear industry. He pointed to the federal Waste Isolation Pilot Plant (WIPP), which houses low-level nuclear fuel; and URENCO, the country’s sole operating commercial enrichment facility, located in Eunice. The Holtec facility would be located about 12 miles from WIPP.

“We have a robust nuclear scientific workforce in our area because of WIPP and because of URENCO. It’s a very good project from that point of view,” Heaton said.

When Holtec began the NRC application process for the facility, the ELEA had the backing of the state government. Then-governor Susana Martinez expressed her support for the project in a 2015 letter to then-DOE Secretary Ernest Moniz, citing “broad support in the region” for the facility and a “significant and growing national need” to house the nuclear waste in an interim storage facility.

Today, a significant chunk of support has vanished, while opposition to the facility has steadily grown. Current Gov. Michelle Lujan Grisham has publicly opposed the project, as has the All Pueblo Council of Governors, the City of Las Cruces, and the county governments of Santa Fe, McKinley and Bernalillo counties; and a slew of local associations, including the New Mexico Cattle Growers’ Association, the New Mexico Farm and Livestock Bureau, and the Permian Basin Petroleum Association. Nationally, the project is also opposed by several environmental and anti-nuclear groups. But with an estimated two years left in the application process, the window to block the project is closing fast.

State has little say in NRC licensing process

Public opposition to nuclear waste has proven to be a significant obstacle for the federal government in establishing a nuclear storage facility. The Yucca Mountain project was deeply unpopular among local communities and local lawmakers, including former Democratic Senate Majority Leader Harry Reid.

That opposition was instrumental to the project’s abandonment. In 2010, Congress completely defunded Yucca Mountain. The Trump administration has since tried to revive Yucca Mountain for a permanent repository, but has failed to secure any new funding for it from Congress.

Holtec’s proposal for southeastern New Mexico, on the other hand, doesn’t require any federal government funding, nor does it require any approval from Congress. Instead, Holtec needs only receive a license from the NRC to temporarily house nuclear storage at the selected site, and that license can be approved without a permanent storage solution existing. Aside from a few state regulatory permits, Holtec’s proposal doesn’t need state approval, either.

“This is a private project, this is a private company dealing with private utilities,” Heaton said. “It’s not a public operation. I think people think this is somehow like WIPP. It’s not.”

NRC public affairs officer David McIntyre told NM Political Report states do have some say in the application process, but said no opposition was presented at the time.

“The NRC’s rules for licensing spent fuel storage facilities also provide opportunity for states or local government entities to intervene in licensing matters through the NRC’s adjudicatory hearing process,” McIntyre said, which occurred under the Martinez administration. McIntyre added that “no state government entities submitted hearing requests” during the hearing process for the Holtec application.

Steinborn said the state should have a larger seat at the table of the NRC’s processes.

“It exposes the real failing of federal law as it stands right now, as a state that could potentially be forced to be the home of a facility like this,” Steinborn said. “The fact that our state government, and our governor, elected by the entire state — her opinion, and that of many of our federal legislators would have no standing whatsoever. It’s really unfair.”

Steinborn introduced legislation during the 2020 session that would have required the state to do an evaluation of this and future proposals. During the session, the state Energy, Minerals and Natural Resources Department (EMNRD) Secretary Sarah Cottrell Propst spoke in support of the bill, though it died in committee during the short session earlier this year.

“That law would have required the state, on behalf of the citizens, our state government to do a thorough evaluation of not only this proposal but other ones that may come in the future,” he said. “Unfortunately, we still hold very little cards, from a regulatory standpoint.”

Communities not giving up

The NRC released a draft environmental impact statement for the Holtec facility at the beginning of the COVID-19 pandemic in early March, but extended the deadline for an additional sixty days. The public comment period, one of the last opportunities for state agencies and residents of New Mexico to weigh in on the proposal, is currently slated to close mid-July.

Heaton is confident the NRC will approve Holtec’s license application. If all goes smoothly, he said construction on the facility could start in late 2022 or early 2023.

Local and national opponents, including Beyond Nuclear and Alliance for Environmental Strategies, raised nearly 50 objections about the license application. The NRC dismissed all those contentions and the commission’s Atomic Safety and Licensing Board declined to hold an evidentiary hearing.

Holtec declined to comment on the objections, citing pending litigation.

Kamps says Beyond Nuclear is appealing the decision at the federal D.C. Court of Appeals. Gardner said her organization isn’t giving up either.

“We’re going through the appeal process,” Gardner said. “I refuse to just sit back and let them come into town without a fight. I don’t want to be a guinea pig.”